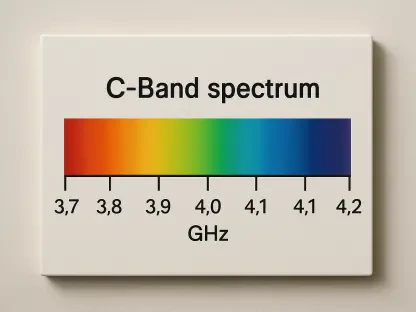

The silent paralysis of a modern economy during a large-scale network outage reveals a fragile dependency on a digital promise that is quietly beginning to fracture. For decades, the telecommunications industry upheld the gold standard of “five nines” reliability, a pledge of 99.999% uptime that translates to a mere 5.26 minutes of potential downtime per year. This bedrock of dependability powered global commerce and communication. Yet, as networks evolve into sprawling, software-defined ecosystems, this long-held assurance is being tested, prompting a critical reevaluation of whether the industry’s most sacred promise is still achievable.

A Fluke Event or a Fundamental Shift

When a network engineered for near-perpetual availability goes dark for ten consecutive hours, it transcends the definition of a simple technical glitch. A single such event mathematically obliterates the five nines standard, plummeting a carrier’s annual reliability from a near-perfect 99.999% to a startlingly low figure closer to 99.8%. This is not just a statistical anomaly; it is a profound deviation that forces a difficult question upon the industry: are these catastrophic failures isolated incidents, or are they symptoms of a deeper, systemic vulnerability inherent in the architecture of modern networks?

The answer appears to lie in the fundamental transformation of network infrastructure itself. The industry has moved decisively away from predictable, hardware-centric systems toward dynamic, multi-layered software environments. This shift has unlocked unprecedented speed and innovation, but it has also introduced a level of complexity that was unimaginable a decade ago. Consequently, the reliability that was once engineered into the physical core of the network is now a function of countless interacting software variables, making the system far more powerful but also exponentially more fragile.

The Vanishing Gold Standard and Why Uptime Is No Longer a Given

The infrastructure underpinning global connectivity has fundamentally changed. Yesterday’s networks were defined by physical boxes and dedicated circuits, where cause and effect were relatively straightforward. Today’s networks are intricate digital biomes, orchestrated by layers of software from numerous vendors running on generalized hardware. This evolution from a tangible to a virtualized state is the primary driver behind the current reliability crisis, turning once-stable systems into dynamic but unpredictable ecosystems.

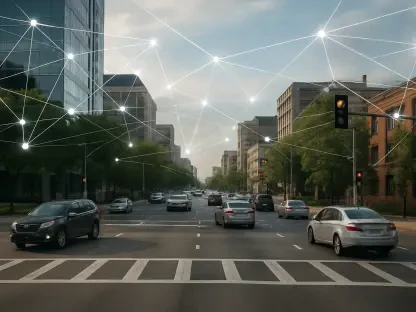

This growing instability arrives at a time of maximum dependency. Critical sectors, including manufacturing, logistics, and energy, are rapidly integrating carrier networks as the central nervous system for Industry 4.0. These industries, which once operated in secure, air-gapped environments, now rely on public and private 5G for real-time automation, remote control systems, and machine-to-machine coordination. The stakes have been raised exponentially, transforming connectivity from a business utility into a foundational element of the physical economy.

As a result, network outages are no longer a temporary inconvenience marked by an inability to browse the web or make a call. They represent a systemic economic risk with the power to halt physical supply chains, idle factories, and disrupt critical energy grids. In this hyper-connected reality, a software bug in a carrier’s core can have cascading consequences that manifest as real-world, kinetic disruptions, making network uptime an issue of national economic security.

Anatomy of a Modern Network Failure

The software revolution has proven to be a double-edged sword for the telecommunications industry. While it has enabled carriers to deploy services with incredible velocity and scale, it has also introduced a degree of operational complexity that often outpaces human comprehension. In this new paradigm, reliability has become an unfortunate casualty, as even the most elite engineering teams struggle to manage systems whose intricate interdependencies defy complete understanding or exhaustive testing.

A recent 10-hour Verizon outage serves as a potent case study. The failure catastrophically dropped the carrier’s reliability from the coveted five nines to what analysts called “two nines and change”—a level of service more akin to unreliable public Wi-Fi. The official cause was a “software issue,” but that simple explanation belies the immense challenge of pinpointing a single fault within a multi-vendor 5G core. The system is a complex tapestry woven from components supplied by Casa Systems, Ericsson, Nokia, Oracle, and Red Hat, all running alongside Verizon’s proprietary software, making root cause analysis a daunting task.

This points to a problem that is not human but structural. Telecom engineers are an elite class of professionals, performing high-stakes work comparable to that of aerospace engineers or power grid operators. However, they are confronting technological headwinds and a rate of complexity that did not exist in prior generations. The challenge is no longer about individual competence but about the structural reality that these digital ecosystems are evolving faster than any organization’s ability to fully control them.

This growing complexity is exacerbated by the dissolution of traditional network boundaries. The clear separation that once existed between a Local Area Network (LAN) and a Wide Area Network (WAN) has all but vanished, creating a single, unified data utility. In this interconnected biome, a failure in one component is no longer contained; instead, it can trigger a cascading, system-wide collapse, demonstrating how localized software issues can have far-reaching and devastating impacts.

The Expert View and the AI Uncertainty Layer

Industry analysts argue that today’s network engineering teams are grappling with a level of intricacy that is simply without precedent. Steve Saunders, a veteran industry observer, compares the complexity of a modern 5G core to that of a nuclear submarine or an advanced EUV lithography machine—systems where absolute precision is non-negotiable. This new environment demands a different approach, as the old models of testing and validation are no longer sufficient to guarantee stability.

Adding another layer of risk is the accelerating integration of artificial intelligence by hyperscale cloud providers. Companies like AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud are positioning Large Language Models (LLMs) as upstream orchestration layers for critical enterprise workflows. These AI systems are designed to interpret unstructured data and make operational decisions for deterministic networks that, by their nature, cannot afford to be wrong downstream. This creates a crisis of trust, where a probabilistic, opaque, and inherently fallible AI can direct a system that demands absolute certainty.

This dynamic introduces an unprecedented “uncertainty layer” into network management. An LLM can be authoritative, persuasive, and entirely incorrect in its reasoning, yet it is being entrusted to guide mission-critical infrastructure. In such a scenario, the reliability of the underlying network becomes almost irrelevant. A five-nines network is of little value if the instructions it receives from its AI orchestrator are fundamentally flawed, creating a new and unpredictable vector for catastrophic failure.

Forging a New Standard in a Converging World

Amid these challenges, a potential silver lining emerges. The erosion of the telco industry’s five-nines standard toward a more realistic four nines (99.99%) could create productive pressure on cloud hyperscalers. These cloud giants have traditionally operated at a lower three-nines (99.9%) standard of reliability. The convergence of these two worlds may compel them to adopt the rigorous, fault-tolerant discipline long practiced by telecom operators to meet the demands of enterprise-grade clients.

This convergence could lead to a blended future where four nines becomes the de facto industry standard—a realistic and achievable middle ground between the historical perfection of telco and the agile-but-less-stable world of the cloud. Such a standard would represent a pragmatic compromise, acknowledging the immense complexity of modern systems while still providing a high degree of dependability for critical applications.

A model for this pragmatic convergence was articulated by John Keib, the head of Google’s fiber network. Despite his background in a hyperscaler culture known for its “move-fast-and-break-things” ethos, Keib has advocated for applying telco-class oversight to critical infrastructure. He acknowledged that full network autonomy may never be desirable or achievable for systems governed by strict Service Level Agreements (SLAs). This embrace of disciplined, human-centric oversight from a leader in the cloud space suggested a path forward. It was a clear signal that the rigor of the old world could temper the ambitions of the new, fostering a hybrid approach that promised to make future networks both innovative and resilient.