I’m thrilled to sit down with Vladislav Zaimov, a seasoned telecommunications specialist whose deep expertise in enterprise telecommunications and risk management of vulnerable networks offers invaluable insights into the ever-evolving wireless industry. Today, we’re diving into the complexities of spectrum deals, rural connectivity challenges, and the competitive dynamics shaping 5G rollouts. Our conversation will explore how massive transactions, like the $23 billion deal between major players, influence market competition, the hurdles of integrating new spectrum bands, and the broader implications for consumers and smaller carriers in rural areas. Vladislav brings a unique perspective to these pressing issues, and I can’t wait to unpack his thoughts.

How do you see a $23 billion spectrum acquisition, like the one involving EchoStar’s 600MHz lowband and 3.45GHz midband licenses, reshaping competition in the wireless industry, and what might this mean for consumer choices over time?

Oh, this kind of deal is a game-changer, no doubt about it. When a major player snaps up spectrum licenses worth $23 billion, especially in the lowband and midband ranges, it’s like adding premium fuel to an already powerful engine. The 600MHz lowband, with its fantastic propagation characteristics, can cover vast areas and penetrate buildings better than higher bands, which means improved 5G performance for users in suburban and rural spots. Meanwhile, the 3.45GHz midband adds capacity for denser, urban environments. This directly strengthens the acquirer’s network, potentially giving them an edge over rivals in terms of coverage and speed—think 80% faster 5G download speeds for mobile services, as we’ve seen reported with some early deployments. But here’s the flip side: it can squeeze smaller competitors who are already spectrum-starved, reducing their ability to compete on quality. For consumers, this could mean better service from the big player in the short term, but less choice down the line if smaller carriers can’t keep up. I remember a similar consolidation years ago with midband spectrum that left regional providers scrambling—some ended up partnering with larger operators just to survive. It’s a double-edged sword, and the FCC’s role in balancing this act is critical.

What are your thoughts on the push for strict geographic coverage conditions, such as achieving 75% geographic coverage for the 600MHz spectrum within five years, as opposed to the more common population-based targets, and what challenges might arise in meeting such mandates?

I think pushing for a 75% geographic coverage target in five years is a bold move, and honestly, it’s a tougher nut to crack than the typical population-based goals like covering 75% of the population by 2030. Population targets are easier because you can focus on urban centers where infrastructure is already dense—hit a few big cities, and you’re done. Geographic coverage, though, forces you to stretch into remote, rural areas where deploying towers and backhaul is a logistical nightmare and often not cost-effective. The challenge here isn’t just the capital investment; it’s also about terrain—think mountains or dense forests—and securing local permissions, which can take months or even years. I’ve seen operators struggle with similar mandates in the past; one carrier I worked with missed a deadline by a wide margin because of unexpected delays in rural zoning approvals. They had the tech ready but couldn’t get the green light to build. Add to that the need for drive tests to verify coverage, and you’ve got a herculean task. It’s a noble goal to ensure rural connectivity, but without flexible timelines or incentives, it risks becoming a penalty trap for operators.

There’s concern from groups like the Rural Wireless Association about spectrum consolidation among major operators potentially harming rural connectivity. How do you envision this playing out for smaller rural carriers, and what steps could help address the imbalance?

Rural carriers are in a tough spot with deals like this, and I feel for them. When spectrum consolidates with the big three, smaller players—often the lifeline for remote communities—get sidelined. Lowband spectrum like 600MHz is gold for rural areas because it travels farther and requires fewer towers, but if it’s hoarded by giants, rural carriers can’t afford to compete or expand. I recall a small carrier in the Midwest a few years back that lost out on a lowband auction and had to lease spectrum at exorbitant rates just to keep their network alive; their customers faced dropped calls and spotty data for years as a result. It’s heartbreaking to see communities left behind like that. To balance this, the FCC could mandate partitioning some spectrum for rural geographic areas, as suggested by some advocacy groups, and enforce good-faith negotiations between big operators and smaller providers. Additionally, reforming resale rules to make it easier for rural carriers to access spectrum via mobile virtual network operator agreements could be a lifeline. It’s about creating a framework where rural connectivity isn’t just an afterthought—it needs to be a priority baked into these deals.

Regarding the rapid deployment of the 3.45GHz midband spectrum to 23,000 sites even before deal approval, resulting in an 80% boost in 5G download speeds, what’s your take on the implications of such a move, and how does this technology translate to tangible benefits for customers?

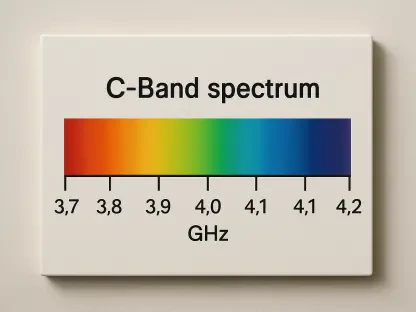

Deploying the 3.45GHz midband spectrum to 23,000 sites before a deal is even finalized is a gutsy move, but it shows confidence in the transaction and a hunger to capitalize on midband’s sweet spot between coverage and capacity. Midband spectrum like this is perfect for urban and suburban areas—it delivers high speeds without needing as many small cells as millimeter wave, and it’s already yielding an 80% jump in 5G download speeds for mobile services, with a 55% increase for fixed wireless access at over 5,300 sites. For customers, this isn’t just a number; it’s streaming a 4K movie without buffering while commuting or running a small business from home with rock-solid connectivity. The tech behind it involves leveraging existing network infrastructure with spectrum manager leases, then upgrading radios and software to handle the new frequencies. Step by step, you’re integrating the spectrum into base stations, optimizing antenna configurations, and rolling out carrier aggregation to combine bands for peak performance. I’ve seen similar rollouts transform user experiences almost overnight—folks in a pilot city I consulted for went from constant frustration to raving about their service in weeks. The risk, though, is if the deal falls through, you’ve invested heavily upfront. Still, for now, it’s a win for users who feel the speed boost immediately.

There’s a suggestion to cancel or reclaim unconstructed 600MHz licenses for re-auctioning to benefit taxpayers. What’s your perspective on this approach, and how might such a process unfold based on past examples?

Reclaiming unconstructed 600MHz licenses for re-auctioning is a provocative idea, and I can see the logic behind ensuring spectrum doesn’t just sit idle while benefiting only corporate coffers instead of taxpayers. Spectrum is a public resource, after all, and if a company isn’t using it as promised, returning it to the pool for others to bid on could generate revenue for the U.S. Treasury and spur innovation. Historically, the FCC has reclaimed unused spectrum before—think of some educational broadcast licenses in the early 2000s that were re-auctioned after sitting dormant. The process typically starts with the FCC issuing a notice of non-compliance, giving the licensee a chance to rectify or forfeit. If forfeited, the spectrum is cataloged, often bundled with other licenses, and put up for auction with clear buildout requirements to avoid repeat hoarding. I remember working on a case where reclaimed spectrum was re-auctioned, and a mid-tier operator snapped it up, deploying services in under two years—it revitalized competition in that region. The challenge is ensuring the process is transparent and doesn’t just favor deep-pocketed players again. It’s a balancing act, but if done right, it could push the industry forward and benefit the public.

With the plan to turn EchoStar into a hybrid mobile operator under the Boost Mobile brand through a wholesale service agreement, how do you think this unique arrangement could influence the market, and what might consumers experience as a result?

This hybrid mobile operator setup with EchoStar under the Boost Mobile brand is fascinating—it’s like a restaurant franchising its kitchen but using someone else’s dining room. EchoStar will run its own core network while leaning on a major operator’s radio network through a wholesale agreement, which could lower their operational costs significantly. This arrangement might shake up the market by injecting more competitive pressure—Boost Mobile could offer aggressive pricing or innovative plans since they’re not burdened with the full cost of infrastructure. Think of it like the early days of mobile virtual network operators piggybacking on larger carriers; I saw one disruptor slash prepaid plan prices by 30% a decade ago, forcing bigger players to respond with better deals. For consumers, this could mean more affordable options or better service reliability, especially if EchoStar focuses on underserved niches. The potential downside is if service quality dips during integration—mismatched networks can lead to hiccups. It unfolds in stages: first, aligning core and radio networks, then branding and marketing the service, and finally scaling customer acquisition. If executed well, it could be a blueprint for future partnerships, but it needs careful oversight to ensure consumers aren’t caught in technical growing pains.

Given the commitment to cover 75% of the population with the 600MHz spectrum by 2030, especially since this band isn’t currently supported by the existing network, what are the key technical and operational hurdles in this rollout, and how might they be addressed?

Rolling out the 600MHz spectrum to cover 75% of the population by 2030 is an ambitious target, especially since the network doesn’t currently support this band. The biggest hurdle is the hardware—existing radio equipment isn’t tuned for 600MHz, so you’re looking at a massive upgrade cycle across thousands of sites. Step one is deploying new radios and antennas compatible with lowband frequencies, which requires not just capital but also meticulous planning to minimize downtime. Step two is optimizing the network for propagation; this band travels farther, so tower placement and interference management become critical. Then, there’s the backhaul challenge—ensuring rural sites have the fiber or microwave links to handle increased traffic. I recall a project where a carrier underestimated backhaul needs for a lowband rollout, and speeds tanked despite great coverage; it took them an extra year to retrofit. Operationally, securing permits for new sites or upgrades in remote areas can be a slog—local pushback is real. Addressing this means staggered deployments, starting with high-impact areas, and partnering with local governments for smoother approvals. It’s a grind, but with phased investments and clear milestones, it’s doable. The payoff—reliable 5G in places that’ve never had it—will be worth the sweat.

Looking ahead, what is your forecast for the future of spectrum allocation and competition in the wireless industry as these large-scale deals and technological advancements continue to unfold?

I see the future of spectrum allocation and competition in the wireless industry as a high-stakes chess game, with even more consolidation on the horizon unless regulators step in with creative solutions. As 5G matures and 6G looms, demand for spectrum—especially lowband and midband—will only intensify, pushing more mega-deals like this $23 billion transaction. Without checks, we risk a market where three or four giants hold all the cards, leaving smaller players and rural connectivity in the dust. I predict the FCC will increasingly use tools like spectrum partitioning and mandatory sharing agreements to level the field, though enforcement will be key. Technologically, advancements in dynamic spectrum sharing could ease some pressure by letting multiple operators use the same frequencies more efficiently—I’ve seen early trials where this boosted capacity by 20% in dense areas. But the human element can’t be ignored; communities and smaller carriers need a voice at the table. My hope is we’ll see a hybrid model emerge, blending public-private partnerships to ensure spectrum serves both profit and the public good. If not, we’re headed for a winner-takes-all scenario, and that’s a loss for innovation and equity.